Prioritisation is all about making decisions. What should we do? When must we do it? Decision making in any area of life can be – and often is – stressful. This is especially true in business, where company profitability, customer satisfaction and employee contentment are all affected by decisions taken by fallible human beings with imperfect knowledge.

The more complex the situation, the more information available, the more individuals involved in the decision-making, the more difficult is all becomes. Ask any military strategist or general.

The ICE FRAMEWORK (based on the well known DFV framework) offers a way to take team ideas for innovating and growing your company, and to prioritise them using the available data (information). It facilitates the ranking, and thereafter the prioritising, of the tactics which will be used in gaining a particular objective. However, simply ranking tactics will not miraculously deliver the strategy which is necessary to operationalise the tactics. As Sun Tzu noted in The Art of War, tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat. TACTICS NEED TO BE INTERCONNECTED AND ALIGNED WITH ACHIEVING GOALS.

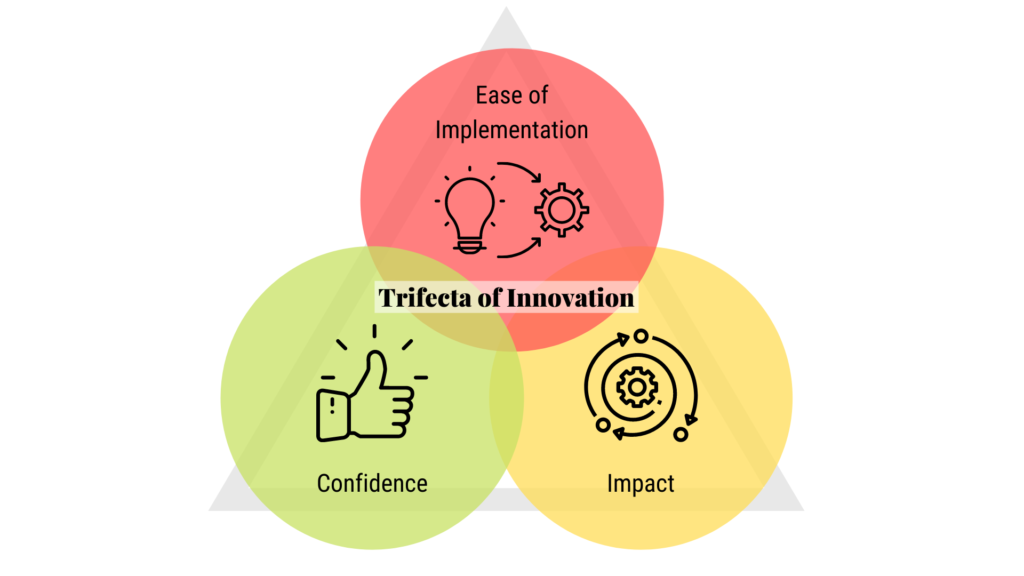

The Venn diagram, above, shows the ICE framework. It reminds the decision makers of the questions they should be constantly asking about each new idea and suggestion for growth or innovation:

-

If this works, how big will the impact be? Will it be profitable and sustainable? Will it have long-term viability in the organisation?

-

How confident are the decision makers that this is likely to succeed? Is it a desirable solution – one the customers really need, or something they might just want? Will the innovation solve the key customer problems?

-

How many resources will be required to implement this? Is its implementation feasible? Is it playing to the organisation’s operational capabilities? A solution which works for one organisation with particular internal and external strengths might not work for another. If a solution/innovation is not congruent with the organisation’s existing operational strategies, it will require the building of a new set of capabilities. The investment then becomes riskier because of the resources required, and this new course of action could alter the market’s perception of the company – and not necessarily for the better.

ICE scoring was developed by marketers so that engineers would listen to their requests. It has been seen as an engineer’s way of approaching growth strategy and should be ideally suited to building bridges or technology companies. After all, engineers are data-driven, and the ICE framework ultimately relies on as much information as possible.

- Lists of ideas to be tested are brainstormed.

- An ICE score/10 for each test idea, or tactic, is calculated. Each tactic is scored for impact, ease of implementation and confidence. The scores are totaled and averaged.

- The test ideas which score highest are then prioritised and adopted. The framework aims to identify those ideas which will have the greatest impact and be easiest to implement, while costing less and taking less time to operationalise.

There are advantages to using an ICE framework, particularly in an agile setting:

- Every employee’s ideas have a chance to be considered and rated.

- It enables the best ideas to rise to the top, no matter where they come from.

- Agile teams are able to take on the tasks from the top of the list, so are sure of working on the most valuable, or important, tasks.

In fact, the ICE framework is not that different from several other processes which have been developed over the years, such as:

- Rational choice theory, or optimisation, was developed in economics. It assumes that all people are rational and have perfect information, which costs nothing. It only works in simpler models of reality by identifying and evaluating options; weighing up the different aspects; producing ratings and choosing the alternative that scores the most.

- Satisficing selects the dominant plan in conditions of uncertainty, contrasting with optimisation.

-

Cost-benefit analysis has been applied widely.

The ICE framework seems to be a fairly simple, fail-safe method of prioritisation. It is thorough and all-inclusive. It is also a long and laborious process, and a time-consuming one.

Unfortunately, research has shown that decision makers in critical situations do not use anything like these models. Individuals who are required to make snap decisions every day (parameds, firefighters, army generals) visualise potential solutions and choose the first workable solution, in an instant. They juggle complex goals in high-stakes, time-pressured situations which change constantly; yet research has shown that they routinely make good decisions. They avoid the paralysis that comes with self-doubt and do not seek the best possible outcome.

How do they do it? This is a question Malcolm Gladwell asked, and answered, in his bestseller Blink.

Daniel Kahneman speaks of ‘fast thinking’ and ‘slow thinking’ – which are lodged in opposite sides of our brain. Fast thinking refers to our brain’s first, automatic, intuitive response. This is how we can make snap decisions. Slow thinking refers to our brain’s slower, analytical mode, where reason and superior computing power dominate. So it should be better for solving complex problems. Right? Not really. Complex problems are by definition, ‘unknowable’, so logic and analytical thinking are only useful to a point. Logic can be applied to probe the problem, to consciously interpret it, and to respond… to a point.

Few experienced, successful decision makers, if asked, are able to explain or justify the decisions they have taken. Often, they offer logical, analytical reasons for their decisions, which appear to have been taken without due consideration. It seems that experienced decision makers use fast thinking – intuition and emotion. Yet they make wise decisions. This feels counter-intuitive. HOW DO THEY DO IT? They have spent years analysing and solving complex problems. They remember and have learnt to recognise the right solutions and therefore automatically make wise decisions. BUT THIS TAKES YEARS OF PRACTICE.

Where does this leave the novice decision maker who is unfamiliar with systems and patterns? Without the benefit of experience, the beginner decision maker needs the impartial assistance of a system, such as the ICE framework. This formalises a ranking strategy and guides a thorough consideration of the problem. However, the rankings arrived at will actually be subjective and inconsistent and only give the illusion of being data-driven.

So make good use of the ICE framework, but remember:

- If you are too rational and efficient, you become predictable. This can threaten your survival.

- Emotion is key to our ability to survive and thrive. It enables us to model, predict and anticipate complex situations and problems. EMBRACE EMOTION AND INTUITION.

- Remember that timing can be everything. The D-Day landings were rescheduled to coincide with a break in the weather – and they succeeded.

- Be flexible. Conditions change constantly. You need to be able to adjust and adapt.

- Constant learning and innovation must become a part of any decision making and prioritisation.

Further reading

Gladwell, Malcolm. Blink: The power of thinking without thinking. 2006

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan, 2011.

Orton, Kirstan, Desirability, Feasibility, Viability: The Sweet Spot for Innovation, Inceodia, 2017

Back to the Table of Contents of our Techno Fluency book