Here is the question: “What is the difference between lean and Kanban? Answer: lean is a destination; Kanban is a means to get there" – David J. Anderson

This blog post is an attempt to clarify how lean and Kanban fit together. It’s easy to oversimply the answer, and it’s also easy to go down a rabbit hole as there is so much philosophy and thought hidden beneath these words.

We should probably start with a definition as to what lean is. Well, that is easy, google the term, and Bob’s your uncle….. You are probably laughing at this point as you have done just that on previous occasions and came away with no concise definition.

What is Lean?

I would suggest that we start with Toyota and move on to the published works of James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones. You see, these two gents were quite intrigued with how Toyota revolutionized their manufacturing by a system called the Toyota Production system. Womack and Jones published a book with the title: Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in your Corporation in 1996. This book called Toyota’s production system a “lean system” that contrasted throughout the book with the traditional “mass production” system of manufacturing epitomized by batch-and-queue methods.

The authors argue that a lean way of thinking allows companies to “specify value, line up value creating actions in the best sequence, conduct these activities without interruption whenever someone requests them, and perform them more and more effectively. ” This statement leads to the five principles of lean thinking: Value, Value Stream, Flow, Pull and Perfection.

Value is defined by the authors as a “capability provided to customer at the right time at an appropriate price, as defined in each case by the customer.” Value is the critical starting point for lean thinking, and can only be defined by the ultimate end customer. The ultimate end customer, or the user of the product, is contrasted with interim customers, such as sales, marketing, distribution, suppliers. Value also is product-specific, and the authors argue it is only meaningful when expressed in terms of a specific product.

The value stream is defined in Lean Thinking as the set of all the “specific activities required to design, order, and provide a specific product, from concept to launch, order to delivery, and raw materials into the hands of the customer.” To create a value stream, describe what happens to a product at each step in its production, from design to order to raw material to delivery. There are three types of activities in the value stream – one kind adds value, and the other two are “muda” (the Japanese word for waste):

- Value-Added: Those activities that unambiguously create value

- Type One Muda: Activities that create no value but seem to be unavoidable with current technologies or production assets

- Type Two Muda: Activities that create no value and are immediately avoidable

Some examples of muda are mistakes which require rectification, groups of people in a downstream activity waiting on an upstream activity, or goods which don’t meet the needs of the customer.

The lean principle of flow is defined as the “progressive achievement of tasks along the value stream so that a product proceeds from design to launch, order to delivery and raw materials into the hands of the customer with no stoppages, scrap or backflows.” This translates as a directive to abandon the traditional batch-and-queue mode of thinking that seems common sense to most. Ways to foster flow include enabling quick changes of tools in manufacturing, as well as rightsizing machines and locating sequential steps adjacent to one another.

The fourth lean principle of pull is defined by the authors as a “system of cascading production and delivery instructions from downstream to upstream in which nothing is produced by the upstream supplier until the downstream customer signals a need.” This is in contrast with pushing products through a system, which is unresponsive to the customer and results in unnecessary inventory build-up.

The fifth and final lean principle is perfection, defined again by the authors as the “complete elimination of muda so that all activities along a value stream create value.” This fifth principle makes the pursuit of lean a never-ending process, as there will always be activities that are considered muda in the value stream and the complete elimination of muda is more of a desired end-state than a truly achievable goal.

Personally I believe that this book started the lean thinking movement. Since then lean thinking has been applied to more than just the manufacturing industry.

What is Kanban?

For the original definition of the Kanban method readers are referred to David Anderson’s Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business (Blue Hole Press, 2010).

The following extract is a more condensed definition of Kanban as published in David Anderson and Andy Carmichael’s Essential Kanban Condensed (May 2016):

“Essentially Kanban is a method for defining, managing, and improving services that deliver knowledge work, such as professional services, creative endeavors, and the design of both physical and software products"

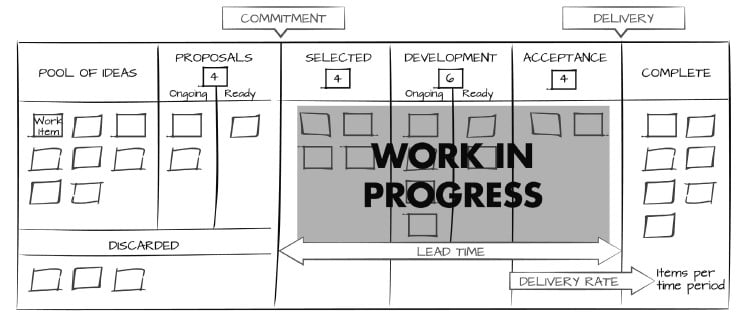

The Kanban Method is based on making visible what is otherwise intangible knowledge work, to ensure that the service works on the right amount of work—work that is requested and needed by the customer and that the service has the capability to deliver. To do this, we use a kanban system—a delivery flow system that limits the amount of work in progress (WiP) by using visual signals.

The signaling mechanisms, sometimes referred to as kanbans, are displayed on kanban boards and represent WiP Limits, which prevent too much or too little work entering the system, thereby improving the flow of value to customers. The WiP Limit policies create a pull system: Work is “pulled” into the system when other work is completed and capacity becomes available, rather than “pushed” into it when new work is demanded.

Kanban focuses on the delivery of services by an organization—one or more people collaborating to produce (usually intangible) work products. A service has a customer, who requests the work or whose needs are identified, and who accepts or acknowledges delivery of the completed work. Even where there is a physical product from services, value resides less in the item itself and more in its informational content (the software, in the most general sense).

The General Practices of Kanban define activities for those managing kanban systems. They are:

- Visualize.

- Limit work in progress.

- Manage flow.

- Make policies explicit.

- Implement feedback loops.

- Improve collaboratively and evolve experimentally.

These practices all involve:

- seeing the work and the policies that determine how it is processed; then

- improving the process in an evolutionary fashion—keeping and amplifying useful change and learning from and reversing ineffective change.

Conclusion

Kanban subscribes to the 5 lean thinking principles of:

- The end customer defines value

- Management of value streams

- Optimizing flow

- Utilization of pull systems

- Pursuit of perfection (continuous improvement)

Lean thinking applied to knowledge work leads to the Kanban method. In other words Kanban is concerned with the design, management, and improvement of flow systems for knowledge work (as opposed to manufacturing work).

This was a guest post by Karl Fuchs, a Lean-Agile coach at Standard Bank South Africa. Karl has deep experience in Programme Management, Lean and Agile practices. Generally a good guy to have around when you want to improve your organisation.