In his book ‘The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization’ Peter Senge says:

“The only sustainable competitive advantage is an organisation's ability to learn faster than the competition.”

But how do we do this? How does an organisation gear itself to being able to not only learn, but learn quickly? There is a strong relationship between a learning organization and an organization which has a culture of continuous improvement. This holy alliance between a learning organisation and continuous improvement can be logically explained. After all, to improve something, one first needs to learn something new and have the willingness to experiment with it. Without learning, continuous improvement will remain ad-hoc, fortuitous and unsustainable.

But this culture doesn’t just happen. It’s not a tool or an app which we can install, go for orientation on and be handed a booklet titled ‘How to do continuous improvement’. It is a culture that is engrained in every level and every facet of your organisation. It is a culture which embraces change, rather than shy away from it.

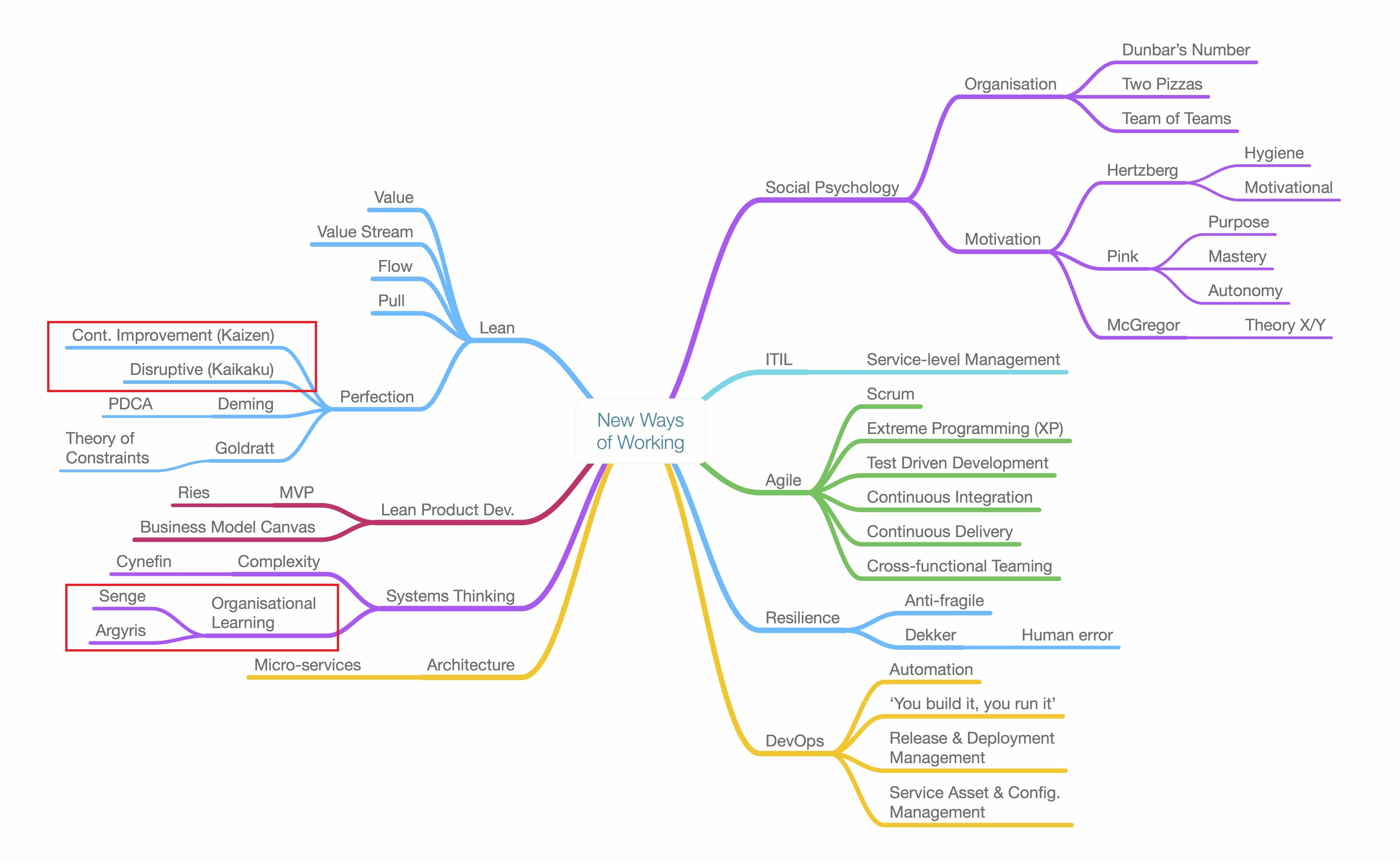

We build on our previous post on new ways of working by providing ways in which an organisation could welcome change which leads to a culture shift towards continuous improvement and ultimately become a learning organisation.

Why a Learning organisation?

Moore’s Law, described in 1965 by Gordon E. Moore the co-founder of Intel, still holds true today. Technological enhancements are doubling approximately every two years. These enhancements are being realized in areas such as processing speeds, memory and connectivity bandwidth. This fact, accompanied with lower than proportionate increase in cost results in a consumer’s ability to access services / information quicker, cheaper, anytime and without sacrificing convenience or quality.

Not only does this result in our customers’ needs changing, but also our actual customers are changing as well. To keep up with these external changes, organisations need to learn and fast. Organisations need to learn what the customers want (the first principle of Lean is ‘The customer defines the value’) and we need to learn a new way of doing things and ultimately adapt the way we work. Therein lies the problem. Adapting implies change and inherently people resist change. Or more accurately according to Peter Senge “People don't resist change. They resist being changed”.

But to improve, we need to apply our new learnings which results in changes in the way we acted before. Simply put, Improvements are applied learning.

Learning + Change = Improvement

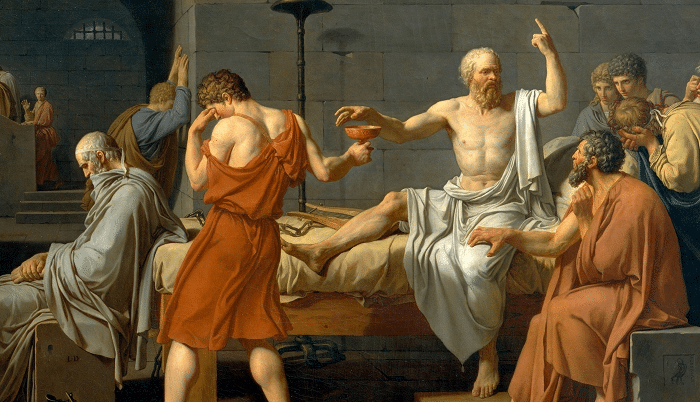

The fear of being changed

Human beings would rather be wrong than uncertain

Consciously we fear change because it introduces uncertainty. Daniel Kahneman in his book ‘Thinking fast and slow’ says that human beings would rather be wrong than uncertain. He in fact goes on to say that our hierarchy of outcomes is to be right (based on our own set of views and paradigms) then to be wrong and lastly to be uncertain.

I’ve seen this fear of uncertainty play out first hand while facilitating a workshop a few years back. I was to change to the flow of work in a delivery team and while running the workshop, the team lead kept on interrupting me with an apparent dire need for me to take into account the work that she needed to do daily on a Work In Progress Report. Eventually I asked her to give me some information about this report that she had been doing since taking over the team lead role eight months earlier. I went on to do some investigation and found that the report wasn’t needed, in fact was a waste and that she should please stop sending it. When I gave her this feedback I was expecting to see relief or even frustration. Instead, what I observed was fear. By telling her that something which she had identified with and gave her a sense of control was about to change, what I did was I had introduced uncertainty. Uncertainty for what was she going to do now, was her role still important, will she be able to do whatever else this change introduces?

There are also other conscious factors such as loss of control, lack of motivation and fatigue or “we’ve tried something like this before, they all failed and so will this”.

Subconsciously we fear change because that’s physiologically how our brains are wired. We trick ourselves into believing that if something’s been the way it is for a while (or decades in some examples) and we’re still alive or perceive ourselves to be delivering value then it must be good enough. The old adage of ‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it’ sits right at the core of this perception. A study in 2010 performed at the University of Kansas found a bias towards things that have been around for longer. One experiment involving acupuncture showed that participants favored it more when they were told it existed for 2000 years as opposed to the group who were told it existed for 250 years. The same bias was seen when a group of participants was given the same chocolate wrapped in different colored wrapping. They were described as one being sold from 73 years ago and the other from just 3. The chocolate that supposedly sold 73 years ago tasted richer and creamier according to the participants!

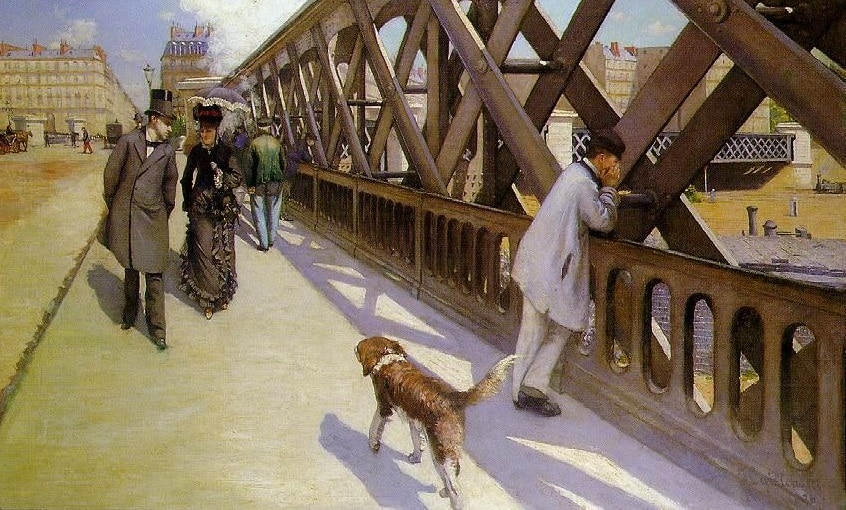

All forms of change invokes some form of stress (even the good changes, like upgrading your car or going on holiday) and this stress triggers one of three reactions.

Fight – Because if it’s something different, I might need to fight it to maintain my safety or maintain my ability to exist. Like a wild cat when we were cavemen or in today’s age to resist new methodologies or technologies.

Flight – Run or hide from a wild cat or delay adopting new technologies, denying any enhancements and backing off into a silo.

Freeze – Just stand really really still, hopefully the wild cat won’t notice me or in today’s organisations pretend not to be aware of changes in technologies and way of working.

These forms of reactions are hardwired into our DNA.

Changing Legacy Systems

Our paradigms are made up of experiences and beliefs that we’ve gained over an extended period of time. The longer we’ve experienced them this way, the more engrained the paradigm is. The same can be said of the cultural paradigm of an organisation. Let’s call these cultural paradigms ‘Legacy Systems’.

The reason why startups encounter less resistance to change is exactly because of this fact. They have smaller and less engrained Legacy Systems. But this is by no means implying that big organisations with their deeply engrained legacy systems cannot change. Big organisations can and have started to change these legacy systems. They do so by adopting evolutionary change rather revolutionary change.

Evolutionary change – This type of change is small, continuous, and gradual and is reliant on the people to perform the change. As a result, it is well adopted by large organisations and becomes the make-up of the new cultural paradigm. In Toyota culture of Kaizen (Kai = Change, Zen = Good). Kaizen is a culture of continuous improvement, in small, sustainable, self-driven iterations using Deming’s scientific method. Kaizen requires empowered employees to firstly identify opportunities for improvement and then have the resources to institute the change. The author Imai (in ‘Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success’) defines kaizen as “organized activities involving everyone in a company- managers and workers, in a totally integrated effort toward improving performance at every level”

Revolutionary changes seldom, if ever become part of the culture of an organisation

Revolutionary change – This is a bigger more radical change and is reliant on the leader to describe and give mandate. These types of changes are often reactionary, i.e. a decline in market share or a department failing an audit. Revolutionary changes seldom, if ever become part of the culture of an organisation. In Toyota this form of change is called Kaikaku.

Change to Learn

Changing the way people think in large organisations is a daunting task yet remains absolutely necessary if we are to stay relevant. Dan Pink says that ‘Management is an invention, much like the television’. Perhaps, what’s happened is that management, the invention has not kept up with the evolution of change in our work and as a result now needs to be revolutionised? Below are some suggestions on how to enable change and learning:

- Create the case for change. What is the desire for this change? Answer the question of “what are the possibilities on the other side of uncertainty?”

- Empower the people. Give people the skills, tools and endorsement to make changes.

- Leaders should be visible and available. Make yourself available for questions, concerns and ideas (Hiroyuku Hiranu said: ‘Ten person’s ideas are better than one person’s knowledge’)

- Create the environment. Create a safe environment for experimentation and even failure without victimization. Favor intrinsic over extrinsic motivators.

- Make the change personal. Understand the individual aversion to this specific change and ask the question “what would you like to see / do differently?”

- Involve the entire organisation, from ‘C level’ execs to junior staff. People want to be heard. This also breaks the notion of ‘Us and them’ or ‘This change is being done to us’.

- Make time for honest reflection or ‘Hansei’ in Japanese. “Hansei is really much deeper than reflection. It is really being honest about your own weaknesses. If you are talking about only your strengths, you are bragging. If you are recognizing your weaknesses with sincerity, it is a high level of strength.” Jeffery Liker, The Toyota Way. Hansei helps you to recognize the problem, take ownership and responsibility of the problem and drives the individual towards a plan of action to improve.

Organisation leaders should understand that there will be resistance to change but resistance should not spell the end for change. Ultimately a realisation that through learning, better ways of work can be achieved.

This was a guest post by Adrian Ryan, a Lean-Agile coach at Standard Bank South Africa. He has a passion for organisational change and is a Six Sigma Ninja.